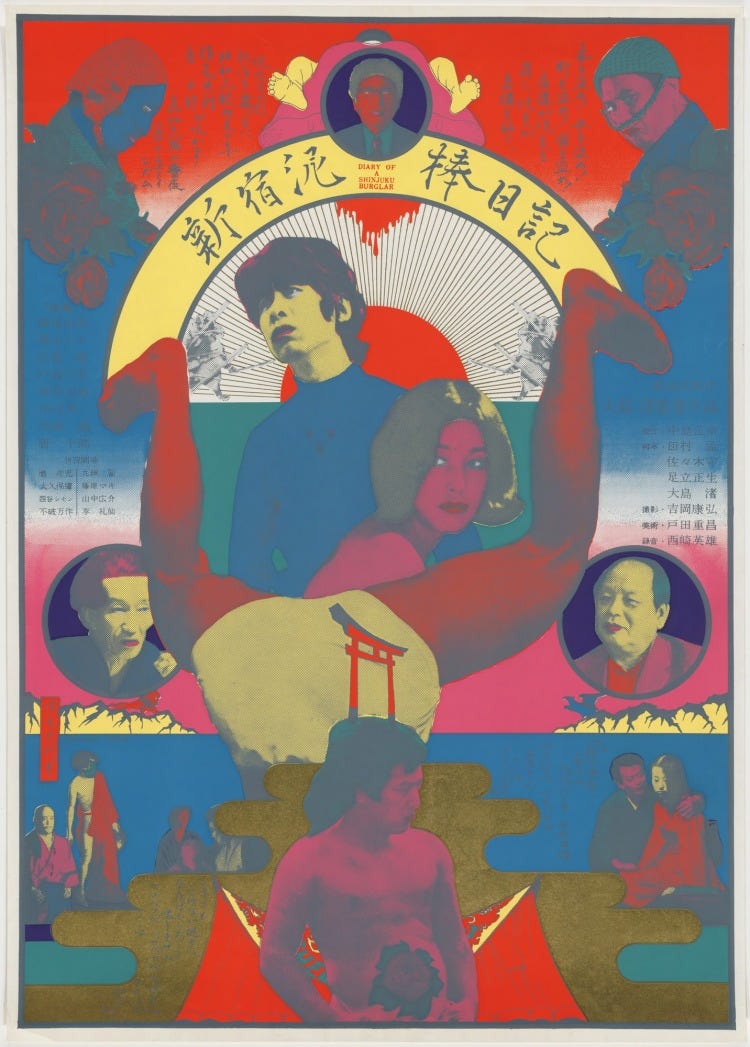

Diary of a Shinjuku Thief by Nagisa Ōshima

Ōshima launched a guerilla assault on narrative continuity and political neutrality in his disruptive tale about two sexually confused deviants traipsing in Shinjuku seeking liberation.

A young man claiming the moniker Birdey Hilltop is caught stealing in a bookstore by a girl falsely claiming to be an employee, Umeko Suzuki, during the summer of 1968; they spend the rest of the movie embarking on an asymptotic journey across Tokyo to reify and sublimate their repressed sexual desires in order to free themselves from the shackles of the social constructs of the previous generation. Their journey takes them through a dizzying mixture of fact and fiction, from an encounter with Tetsu Takahashi, a famous Freudian sexologist, to involvement in a fringe performance of an avant-garde kabuki show by Juro Kara. Finally, Birdey is given a part in the new theater production as a revolutionary hero of the 18th century. During the performance, Birdey and Umeko finally shed their inhibitions and find sexual ecstasy — that night, student riots break out in Shinjuku.

It is crucial to contextualize the zeitgeist undergirding the cloudy narrative of this film, viz., Japan exists as the impenetrable and impregnable island qua maiden with "her legs crossed," as proclaimed by leftist luminaries Juro Kara (underground playwright and theater director) and his Situationist troupe, along with Moichi Tanabe (the real-life bookstore owner), acting as the old guard of sexuality and liberation, all while the student revolution was happening in the background. However, it seems that Oshima is interrogating whether repressed desires frustrate the catalyst for revolution as depicted in his film Sing a Song of Sex, then if so, in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, sexual liberation must precede political revolution.

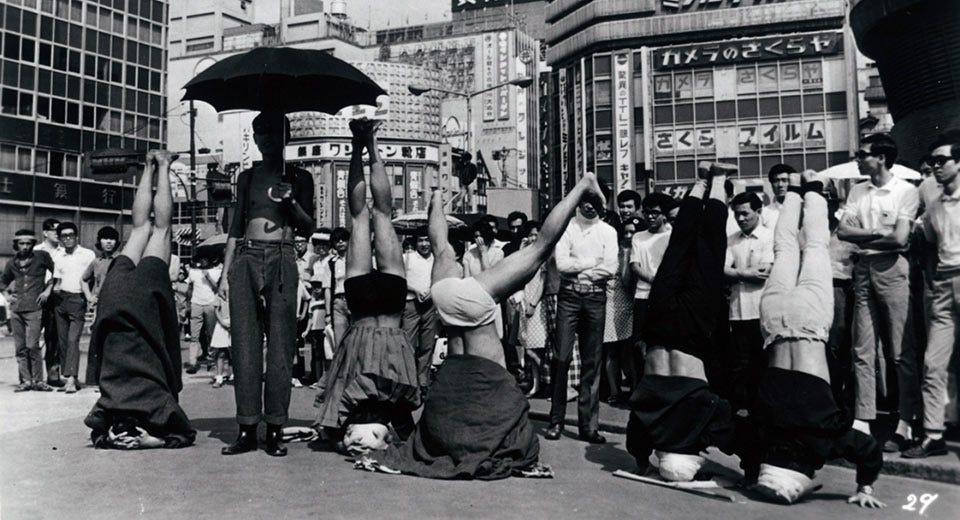

Nagisa Ōshima employs a unique cinematic vocabulary, shifting abruptly from black-and-white to color and meshing naturalistic acting, theatrical intermezzos, and energetic cinéma vérité techniques to capture the violent protests and the radical street theater enacted by Ōshima's cast and, at times, crew.

In Cinema, Censorship, and the State, it is explained that in “In Japanese parlance, 'narrative' means a specific method of storytelling in which the narrator governs the voices of the characters. The modernist novel and the antinovel destroyed the identity of the character and the unity of the authorial voice. Oshima does not cherish the concept of narrative prevalent among film theorists in the West. The concept has no place within a Japanese theory of cinema: its place within Japanese theoretical tradition is confined to literary theory."

Ōshima, in his essay, Is it a Breakthrough? (The Modernists of Japanese Film), reaffirms his aversion of the Western concept of narrative when he writes, “The modernist Masumura turns his back on the overriding lyricism, reality, and atmosphere of the Japanese film and the society that produces it: ‘My goal is to create an exaggerated depiction featuring only the ideas and passions of living human beings.’ Masumura, possessor of the sharpest sociological perceptions of the three [Masumura, Shirasaka, and Nakahira], understood the inevitable: ‘In Japanese society, which is essentially regimented, freedom and the individual do not exist. The theme of the Japanese film is the emotions of the Japanese people, who have no choice but to live according to the norms of that society. The cinema has had no alternative but to continue to depict the attitudes and inner struggles of the people who are faced with and oppressed by complex social relationships and the defeat of human freedom.’”

Diary of a Shinjuku Thief opens—notwithstanding the pre-credits sequence—with a stunning sequence in the bookshop, filmed with a Bressonian insistence on the play of hands. It seems real enough to the viewer. However, the framing of the shot (Birdey now repeating the same accosting gesture Umeko performed on him) suggests a prior complicity between the young couple. Eventually, Mr. Tanabe reveals Umeko never was, in fact, employed at his store, leaving the viewer wondering two questions: When did their game begin, and what is exactly their game? These questions are important because Ōshima is preoccupied with conceiving their masquerade—a la the signifier of Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal—, as a conduit for people to enact their repressed dreams and desires, thus demonstrating the nullity and uselessness of reality.

Suppose Birdey is exorcising his sense of disgust and degradation through his performance as a thief. Then so is Umeko, as her performance as a policeman. Thus, Mr. Tanabe’s, caught between this attempted rejection of hierarchies and superstructures and refusal to be actively involved in their masquerade, is positioned as the bourgeois liberal who refuses to take sides in the dialectal quarrel between youthful modernity and the anachronistic forces of repression. Ōshima makes this point unequivocal by placing this narrative between two contexts: (1) time-checks and weather reports from capitals of the world re-laved over the sound of protesting voices in the background; and (2) the shots of a group of strolling people sounding their revolutionary calls to action in the streets. However, sex appears more obscurely as the catalyst or cathartic agent of revolutionary change since Umeko is arrested after throwing stones at a clock (an homage to the revolutionary actor in the pre-credit sequence) to mitigate her sexual frustration. Subsequently, she and Birdey find ecstasy within the fomenting revolutionary moment, thereby releasing the forces of protest as if they were eagerly waiting for the command.

It is difficult to discern whether Ōshima’s use of sex in Diary of a Shinjuku Thief operates as a source of derision for the revolutionary movement or if he finds sex a source of irony. The pre-credits sequence, designed to make one think one is watching the pursuit and humiliation of a petty thief, in fact, turns out to be a satirical plavlet where the thief suddenly drops his loin-cloth to reveal a chrysanthemum tattooed on the pubic region, at the sight of which (chrysanthemum or pubes, or both?) his captors promptly stand on their heads in awed and abject apology. The scene is compelling enough as revolutionary propaganda: liberating oneself from the oppressive power of the State and rejecting the State's interpellation of the thief. However, since Ōshima has shown in the film that reality is built on sand, constantly blurring with the irreal, the fantastic, and the illusory, is it a legitimate question to think: does Ōshima intend the viewer to break from the fatalistic thinking that the establishment, like the hanged man in his film Death by Hanging, is and will remain alive and kicking regardless of the fomenting revolutionary movement? Indeed, the apparent banalities of the revolutionary play that ultimately uninhibited the repressed desires that Birdey and Umeko have been seeking during the film can hardly be meant as a severe or legitimate threat to organized, capitalist principles.

In contemporary society, capitalism has reappropriated the zeitgeist of sexual liberation and sexuality. So one would be hard-pressed to truly think sexual liberation is, in any way, a threat to capitalism. Moreover, or are we always already waiting for psycho-sexual liberation, hoping we see it on the horizon, but no — every week some new form of the necessity of sexual liberation for people pops up thanks to our capitalist algorithms, constantly delaying the revolution.